Exposure to the Art Treasures of Italy on the Grand Tour Played a Major Role in the Rise of

The Thousand Tour was the principally 17th to early 19th-century custom of a traditional trip through Europe, with Italia as a key destination, undertaken by upper-class immature European men of sufficient ways and rank (typically accompanied by a chaperone, such as a tutor or family member) when they had come of age (about 21 years erstwhile).

The custom—which flourished from nigh 1660 until the advent of large-scale runway transport in the 1840s and was associated with a standard itinerary—served as an educational rite of passage. Though the Grand Tour was primarily associated with the British nobility and wealthy landed gentry, similar trips were made by wealthy young men of other Protestant Northern European nations, and, from the second one-half of the 18th century, by some South and Due north Americans and Filipino Ilustrados.

By the mid-18th century, the 1000 Tour had become a regular feature of aristocratic pedagogy in Central Europe as well, although information technology was restricted to the higher dignity. The tradition declined in Europe as enthusiasm for classical culture waned, and with the advent of attainable track and steamship travel—an era in which Thomas Cook made the "Melt's Tour" of early on mass tourism a catchword starting in the 1870s.

However, with the rising of industrialization in the United States in the 19th century, American Gilded Age nouveau riche adopted the Grand Tour for both sexes and among those of more advanced years as a means of gaining both exposure and clan with the composure of Europe. Even those of lesser means sought to mimic the pilgrimage, as satirized in Mark Twain'due south enormously popular Innocents Abroad in 1869.

The primary value of the Grand Bout lay in its exposure to the cultural legacy of classical antiquity and the Renaissance, and to the aristocratic and fashionably polite order of the European continent. In addition, it provided the just opportunity to view specific works of art, and possibly the only chance to hear certain music.

A 1000 Tour could final anywhere from several months to several years. It was commonly undertaken in the company of a cicerone, a knowledgeable guide or tutor.

History [edit]

Rome for many centuries had already been the destination of pilgrims, especially during Jubilee when European clergy visited the Seven Pilgrim Churches of Rome.

In Britain, Thomas Coryat's travel volume Coryat's Crudities (1611), published during the Twelve Years' Truce, was an early influence on the Grand Tour merely it was the far more than extensive tour through Italy as far as Naples undertaken by the 'Collector' Earl of Arundel, with his married woman and children in 1613–xiv that established the most significant precedent. This is partly because he asked Inigo Jones, non yet established as an builder but already known as a 'great traveller' and masque designer, to human action as his cicerone (guide).[1]

Larger numbers of tourists began their tours after the Peace of Münster in 1648. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first recorded use of the term (maybe its introduction to English language) was by Richard Lassels (c. 1603–1668), an expatriate Roman Catholic priest, in his volume The Voyage of Italy, which was published posthumously in Paris in 1670 and and so in London.[a] Lassels'southward introduction listed four areas in which travel furnished "an accomplished, consummate Traveller": the intellectual, the social, the ethical (by the opportunity of drawing moral pedagogy from all the traveller saw), and the political.

The idea of travelling for the sake of curiosity and learning was a developing idea in the 17th century.

Every bit a swain at the commencement of his account of a echo Grand Bout, the historian Edward Gibbon remarked that "According to the law of custom, and perhaps of reason, foreign travel completes the education of an English gentleman." Consciously adapted for intellectual cocky-improvement, Gibbon was "revisiting the Continent on a larger and more liberal program"; almost Thou Tourists did not break more than briefly in libraries. On the eve of the Romantic era he played a significant part in introducing, William Beckford wrote a vivid account of his Grand Tour that fabricated Gibbon's unadventurous Italian tour look distinctly conventional.[2]

The typical 18th-century opinion was that of the studious observer travelling through strange lands reporting his findings on homo nature for those unfortunates who stayed at domicile. Recounting one's observations to lodge at large to increase its welfare was considered an obligation; the Grand Tour flourished in this mindset.[3]

In essence, the Thou Tour was neither a scholarly pilgrimage nor a religious i,[4] though a pleasurable stay in Venice and a residence in Rome were essential. Catholic Grand Tourists followed the same routes as Protestant Whigs. Since the 17th century, a tour to such places was besides considered essential for budding artists to empathize proper painting and sculpture techniques, though the trappings of the Grand Tour—valets and coachmen, perhaps a cook, certainly a "conduct-leader" or scholarly guide—were across their reach.

The advent of popular guides, such as the volume An Account of Some of the Statues, Bas-Reliefs, Drawings, and Pictures in Italy published in 1722 by Jonathan Richardson and his son Jonathan Richardson the Younger, did much to popularise such trips, and following the artists themselves, the elite considered travel to such centres as necessary rites of passage. For gentlemen, some works of art were essential to demonstrate the breadth and smoothen they had received from their tour.

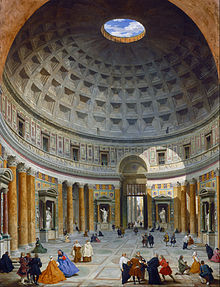

The Grand Tour offered a liberal teaching, and the opportunity to acquire things otherwise unavailable, lending an air of accomplishment and prestige to the traveller. One thousand Tourists would render with crates full of books, works of art, scientific instruments, and cultural artefacts – from snuff boxes and paperweights to altars, fountains, and statuary – to exist displayed in libraries, cabinets, gardens, drawing rooms, and galleries built for that purpose. The trappings of the K Tour, especially portraits of the traveller painted in continental settings, became the obligatory emblems of worldliness, gravitas and influence. Artists who particularly thrived on the Grand Tour marketplace included Carlo Maratti, who was beginning patronised by John Evelyn every bit early as 1645,[5] Pompeo Batoni the portraitist, and the vedutisti such as Canaletto, Pannini and Guardi. The less well-off could return with an album of Piranesi etchings.

The "perchance" in Gibbon's opening remark cast an ironic shadow over his resounding statement.[6] Critics of the Thou Tour derided its lack of adventure. "The tour of Europe is a paltry thing", said one 18th century critic, "a tame, uniform, unvaried prospect".[7] The G Tour was said to reinforce the old preconceptions and prejudices about national characteristics, as Jean Gailhard's Compleat Gentleman (1678) observes: "French courteous. Spanish lordly. Italian amorous. High german clownish."[7] The deep suspicion with which Bout was viewed at abode in England, where information technology was feared that the very experiences that completed the British gentleman might well undo him, were epitomised in the sarcastic nativist view of the ostentatiously "well-travelled" maccaroni of the 1760s and 1770s.

Also worth noticing is that the K Tour not only fostered stereotypes of the countries visited but also led to a dynamic of dissimilarity between northern and southern Europe. By constantly depicting Italy as a "picturesque place", the travellers also unconsciously degraded Italian republic as a place of backwardness.[8] This unconscious degradation is best reflected in the famous verses of Lamartine in which Italian republic is depicted as a "land of the past... where everything sleeps."[nine]

In Rome, antiquaries like Thomas Jenkins were also dealers and were able to sell and propose on the purchase of marbles; their price would rise if it were known that the Tourists were interested. Coins and medals, which formed more portable souvenirs and a respected gentleman'due south guide to ancient history were besides popular. Pompeo Batoni made a career of painting the English milordi posed with graceful ease amid Roman antiquities. Many continued on to Naples, where they also viewed Herculaneum and Pompeii, but few ventured far into Southern Italian republic, and fewer yet to Greece, and so still under Turkish rule.

After the advent of steam-powered transportation around 1825, the 1000 Tour custom continued, merely information technology was of a qualitative difference — cheaper to undertake, safer, easier, open to anyone. During much of the 19th century, almost educated immature men of privilege undertook the Grand Tour. Germany and Switzerland came to be included in a more broadly defined circuit. Later, it became fashionable for young women every bit well; a trip to Italian republic, with a spinster aunt as chaperone, was part of the upper-class women's education, as in E. Grand. Forster's novel A Room with a View.

British travellers were far from alone on the roads of Europe. On the opposite, from the mid-16th century, the grand bout was established as an ideal way to finish off the education of immature men in countries such every bit Kingdom of denmark, France, Germany, kingdom of the netherlands, Poland and Sweden.[ten] In spite of this the majority of enquiry conducted on the Grand Tour has been on British travellers. Dutch scholar Frank-van Westrienen Anna has made note of this historiographic focus, challenge that the scholarly understanding of the Grand Tour would have been more complex if more comparative studies had been carried out on continental travellers.[11]

Contempo scholarship on the Swedish aristocracy has demonstrated that Swedish aristocrats, though being relatively poorer than their British peers, from around 1620 and onwards in many ways acted every bit their British counterparts. Afterward studies at one or 2 renowned universities, preferably those of Leiden and Heidelberg, the Swedish m tourists fix off to France and Italy, where they spent time in Paris, Rome and Venice and completed the original grand bout on the French countryside.[12] King Gustav Iii of Sweden made his M Bout in 1783–84.[thirteen]

Typical itinerary [edit]

The itinerary of the Grand Tour was non set in stone, simply was subject to innumerable variations, depending on an private's interests and finances, though Paris and Rome were popular destinations for about English tourists.

The most common itinerary of the Grand Tour[xiv] shifted beyond generations, simply the British tourist commonly began in Dover, England, and crossed the English Aqueduct to Confirm in Belgium,[b] or to Calais or Le Havre in France. From there the tourist, usually accompanied by a tutor (known colloquially as a "bear-leader") and (if wealthy plenty) a troop of servants, could rent or acquire a double-decker (which could be resold in whatever metropolis – as in Giacomo Casanova'south travels – or disassembled and packed across the Alps), or he could opt to brand the trip by riverboat as far as the Alps, either travelling up the Seine to Paris, or up the Rhine to Basel.

Upon hiring a French-speaking guide, every bit French was the dominant language of the elite in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries, the tourist and his entourage would travel to Paris. At that place the traveller might undertake lessons in French, dancing, fencing, and riding. The appeal of Paris lay in the sophisticated language and manners of French high society, including courtly beliefs and style. This served to polish the immature human'south manners in preparation for a leadership position at domicile, often in government or diplomacy.

From Paris he would typically sojourn in urban Switzerland, often in Geneva (the cradle of the Protestant Reformation) or Lausanne.[fifteen] ("Alpinism" or mountaineering developed afterwards, in the 19th century.) From there the traveller would endure a hard crossing over the Alps (such equally at the Great St Bernard Pass), which required dismantling the wagon and larger luggage.[15] If wealthy enough, he might be carried over the hard terrain by servants.

Once in Italy, the tourist would visit Turin (and sometimes Milan), so might spend a few months in Florence, where at that place was a considerable Anglo-Italian society accessible to travelling Englishmen "of quality" and where the Tribuna of the Uffizi gallery brought together in ane infinite the monuments of High Renaissance paintings and Roman sculpture. Afterward a side trip to Pisa, the tourist would movement on to Padua,[16] Bologna, and Venice. The British idea of Venice as the "locus of decadent Italianate allure" made it an image and cultural set piece of the Grand Tour.[17] [18]

From Venice the traveller went to Rome to study the ancient ruins and the masterpieces of painting, sculpture, and architecture of Rome'southward Medieval, Renaissance, and Baroque periods. Some travellers also visited Naples to study music, and (after the mid-18th century) to appreciate the recently discovered archaeological sites of Herculaneum and Pompeii,[nineteen] and perhaps (for the adventurous) an ascent of Mount Vesuvius. After in the menstruation, the more adventurous, particularly if provided with a yacht, might attempt Sicily to see its archeological sites, volcanoes and its baroque compages, Malta[20] or fifty-fifty Hellenic republic itself. But Naples – or after Paestum further south – was the usual terminus.

Returning northward, the tourist might recross the Alps to the High german-speaking parts of Europe, visiting Innsbruck, Vienna, Dresden, Berlin and Potsdam, with perhaps a catamenia of written report at the universities in Munich or Heidelberg. From in that location, travellers could visit Holland and Flemish region (with more than gallery-going and art appreciation) before returning across the Channel to England.

Published accounts [edit]

William Beckford'south 1780-1781 Grand Tour through Europe shown in ruby

Published accounts of the Grand Tour provided illuminating detail and an often polished first-paw perspective of the experience. Examining some accounts offered by authors in their ain lifetimes, Jeremy Black[21] detects the element of literary artifice in these and cautions that they should be approached as travel literature rather than unvarnished accounts. He lists as examples Joseph Addison, John Andrews,[22] William Thomas Beckford (whose Dreams, Waking Thoughts, and Incidents [23] was a published account of his messages back home in 1780-1781, embellished with stream-of-consciousness associations), William Coxe,[24] Elizabeth Craven,[25] John Moore, tutor to successive dukes of Hamilton,[26] Samuel Jackson Pratt, Tobias Smollett, Philip Thicknesse,[27] and Arthur Young.

Although Italy was written as the "sink of iniquity", many travelers were non kept from recording the activities they participated in or the people they met, especially the women they encountered. To the M Tourists, Italy was an anarchistic country, for "The shameless women of Venice made it unusual, in its own way."[28] Sir James Hall confided in his written diary to comment on seeing "more handsome women this 24-hour interval than I e'er saw in my life", also noting "how flattering Venetian dress [was] — or peradventure the lack of it".[28]

Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Italian women, with their unfamiliar methods and routines, were opposites to the western dress expected of European women in the eighteenth and nineteenth century; their "foreign" means led to the documentation of encounters with them, providing published accounts of the Yard Bout.

James Boswell courted noble ladies and recorded his progress with his relationships, mentioning that Madame Micheli "Talked of religion, philosophy... Kissed mitt oft." The promiscuity of Boswell'due south encounters with Italian elite are shared in his diary and provide further detail on events that occurred during the Grand Bout. Boswell notes "Yesterday morning with her. Pulled upwards petticoat and showed whole knees... Touched with her goodness. All other liberties exquisite."[28] He describes his time with the Italian women he encounters and shares a part of history in his written accounts.

Lord Byron's letters to his mother with the accounts of his travels have also been published. Byron spoke of his start enduring Venetian dearest, his landlord'south wife, mentioning that he has "fallen in love with a very pretty Venetian of two and twenty — with neat blackness optics — she is married — and so am I — we accept found & sworn an eternal attachment ... & I am more in love than ever... and I verily believe we are one of the happiest unlawful couples on this side of the Alps."[29] Many tourists enjoyed sexual relations while abroad but to a slap-up extent were well behaved, such as Thomas Pelham, and scholars, such as Richard Pococke, who wrote lengthy messages of their Grand Bout experiences.[30]

Inventor Sir Francis Ronalds' journals and sketches of his 1818–twenty bout to Europe and the Near East accept been published online.[31] [32] The letters written by sisters Mary and Ida Saxton of Canton, Ohio in 1869 while on a vi-month tour offer insight into the G Tour tradition from an American perspective.[33]

Immediately following the American Ceremonious War U.Southward. writer and humorist Mark Twain undertook a decidedly minor yet greatly aspiring "chiliad tour" of Europe, the Middle East, and the Holy Land, which he chronicled in his highly popular satire Innocents Away in 1867. Not only was information technology the best-selling of Twain's works during his lifetime,[34] it became 1 of the best-selling travel books of all time.[35]

In literature [edit]

Margaret Mitchell's American Ceremonious State of war-based novel, Gone With The Wind, makes reference to the Grand Tour. Stuart Tartleton, in a conversation with his twin brother, Brent, suspects that their female parent is not probable to provide them with a Thousand Bout, since they have been expelled from college again. Brent is not concerned, remarking, "What is there to come across in Europe? I'll bet those foreigners can't show us a matter nosotros haven't got right hither in Georgia". Ashley Wilkes, on the other manus, enjoyed the scenery and music he encountered on his Grand Tour and was always talking about information technology.[ citation needed ]

On television [edit]

In 1998, the BBC produced an art history series Sister Wendy's K Tour presented by British Carmelite nun Sister Wendy. Ostensibly an art history series, the journey takes her from Madrid to Petrograd with stop-offs to run into the great masterpieces.

In 2005, British art historian Brian Sewell followed in the footsteps of the K Tourists for a 10-role television series Brian Sewell's M Bout. Produced by UK's Aqueduct Five, Sewell travelled by machine and bars his attending solely to Italy stopping in Rome, Florence, Naples, Pompeii, Turin, Milan, Cremona, Siena, Bologna, Vicenza, Paestum, Urbino, Tivoli and concluding at a Venetian masked brawl. Material relating to this tin be found in the Brian Sewell Archive held past the Paul Mellon Center for Studies in British Art.

In 2009, the Yard Tour featured prominently in a BBC/PBS miniseries based on Petty Dorrit by Charles Dickens. Set mainly in Venice, it portrayed the Grand Tour every bit a rite of passage.

Kevin McCloud presented Kevin McCloud'southward Grand Tour on Channel 4 in 2009 with McCloud retracing the tours of British architects.

The 2016 Amazon motoring programme The Grand Tour is named after the traditional Grand Tour, and refers to the show being gear up in a different location worldwide each week.

Run across also [edit]

- Gap year

- Hiking § History

- Hippie trail

- Walking tour

- Overseas experience

- Field trip

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ Anthony Forest reported that the book was "esteemed the all-time and surest Guide or Tutor for immature men of his Time." see Edward Chaney, "Richard Lassels", ODNB, and idem, The Grand Bout and the Not bad Rebellion (Geneva, 1985)

- ^ Ostend was the starting indicate for William Beckford on the continent.

References [edit]

Notes [edit]

- ^ East. Chaney, The Evolution of the Grand Tour, 2nd ed. (2000) and idem, Inigo Jones's "Roman Sketchbook", 2 vols (2006)

- ^ Eastward. Chaney, "Gibbon, Beckford and the Estimation of Dreams, Waking Thoughts and Incidents", The Beckford Gild Annual Lectures (London, 2004), pp. 25–50.

- ^ Paul Fussell (1987), p. 129.

- ^ "Pilgrimages". Newadvent.org. Retrieved 2012-07-20 .

- ^ E. Chaney, The Evolution of English Collecting

- ^ Noted by Redford 1996, Preface.

- ^ a b Bohls & Duncan (2005)

- ^ Nelson Moe, "Italy as Europe's South", in The View from Vesuvius, Italian Civilisation and the Southern Question, University of California Press, 2002

- ^ Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Italy Journeying

- ^ Grand Tour : adeliges Reisen und europäische Kultur vom fourteen. bis zum 18. Jahrhundert : Akten der internationalen Kolloquien in der Villa Vigoni 1999 und im Deutschen Historischen Institut Paris 2000. Boom-boom, Rainer, 1955-, Paravicini, Werner. Ostfildern: Thorbecke. 2005. ISBN3799574549. OCLC 60520500.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Anna., Frank-van Westrienen (1983). De groote tour : tekening van de educatiereis der Nederlanders in de zeventiende eeuw. Amsterdam: Noord-Hollandsche Uitgeversmaatschappij. ISBN044486573X. OCLC 19057035.

- ^ Winberg, Ola (2018). Den statskloka resan : adelns peregrinationer 1610–1680. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN9789151302898. OCLC 1038629353.

- ^ "Gustav Three and the Museum of Antiquities - Kungliga slotten". www.kungligaslotten.se . Retrieved 2019-06-03 .

- ^ See Fussell (1987), Buzard (2002), Bohls and Duncan (2005)

- ^ a b Towner, John. "THE 1000 Tour A Key Phase in the History of Tourism" (PDF). Register of Tourism Research. Vol. 12, pp. 297–333. 1985. J. Jafari and Pergamon Printing Ltd. Retrieved 12 December 2012. [ permanent dead link ]

- ^ The Registro dei viaggiatori inglesi in Italy, 1618–1765, consists of 2038 autograph signatures of English and Scottish visitors, some of them scholars, to be certain. (J. Isaacs, "The Earl of Rochester'southward Grand Bout" The Review of English Studies iii. 9 [January 1927:75–76]).

- ^ Redford, Bruce. Venice and the Chiliad Tour. Yale University Printing: 1996.

- ^ Eglin, John. Venice Transfigured: The Myth of Venice in British Culture, 1660–1797. Macmillan: 2001.

- ^ "The captured cargo that unpacks the spirit of the grand bout". The guardian . Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ Freller, Thomas (2009). Malta & The Grand Tour. Malta: Midsea Books. ISBN9789993272489. Archived from the original on 2016-11-08.

- ^ Blackness, "Fragments from the K Tour" The Huntington Library Quarterly 53.4 (Autumn 1990:337–341) p 338.

- ^ Andrews, A Comparative View of the French and English Nations in their Manners, Politics, and Literature, London, 1785.

- ^

- Dreams, Waking Thoughts, and Incidents at Project Gutenberg

- ^ Coxe, Sketches of the Natural, Political and Civil State of Switzerland London, 1779; Travels into Poland, Russian federation, Sweden and Denmark London, 1784; Travels in Switzerland London, 1789. Coxe'due south travels range far from the Grand Tour design.

- ^ Craven, A Journey through the Crimea to Constantinople London 1789.

- ^ Moore, A View of Society and Manners in Italy; with Anecdotes relating to some Eminent Characters London, 1781

- ^ Thicknesse, A Twelvemonth's Journey through France and Part of Spain, London, 1777.

- ^ a b c Iain Gordon Brownish, "Water, Windows, and Women: The Significance of Venice for Scots in the Historic period of the Grand Tour," Eighteenth-Century Life, November 07, 2006, http://muse.jhu.edu/commodity/205844.

- ^ George Gordon Byron and Leslie A. Marchand, Byron's Letters and Journals: The Complete and Unexpurgated Text of All Letters Available in Manuscript and the Full Printed Version of All Others (Newark: Academy of Delaware Press, 1994).

- ^ Jeremy Blackness, Italy and the Grand Tour (New Haven: Yale University Printing, 2003), 118-120.

- ^ "Sir Francis Ronalds' One thousand Tour". Sir Francis Ronalds and his Family unit . Retrieved 9 Apr 2016.

- ^ Ronalds, B.F. (2016). Sir Francis Ronalds: Male parent of the Electrical Telegraph. London: Imperial College Press. ISBN978-1-78326-917-4.

- ^ Belden, Grand Tour of Ida Saxton McKinley and Sister Mary Saxton Hairdresser 1869 (County, Ohio) 1985.

- ^ Norcott-Mahany, Bernard (fourteen November 2012) "Classic Review: Innocents Abroad by Mark Twain." The Kansas City Public Library (Retrieved 27 April 2014)

- ^ Melton, Jeffery Alan (The University of Alabama Press; Tuscaloosa, Alabama 2002) Marker Twain, Travel Books, and Tourism: The Tide of a Great Popular Movement. Projection MUSE (Retrieved 27 Apr 2014.)

Sources [edit]

- Elizabeth Bohls and Ian Duncan, ed. (2005). Travel Writing 1700–1830 : An Anthology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-284051-7

- James Buzard (2002), "The Chiliad Tour and after (1660–1840)", in The Cambridge Companion to Travel Writing. ISBN 0-521-78140-X

- Paul Fussell (1987), "The Eighteenth Century and the Grand Tour", in The Norton Book of Travel, ISBN 0-393-02481-4

- Edward Chaney (1985), The Grand Bout and the Great Rebellion: Richard Lassels and 'The Voyage of Italian republic' in the seventeenth century(CIRVI, Geneva-Turin, 1985.

- Edward Chaney (2004), "Richard Lassels": entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- Edward Chaney, The Development of the Grand Tour: Anglo-Italian Cultural Relations since the Renaissance (Frank Cass, London and Portland OR, 1998; revised edition, Routledge 2000). ISBN 0-7146-4474-9.

- Edward Chaney ed. (2003), The Evolution of English Collecting (Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2003).

- Edward Chaney and Timothy Wilks, The Jacobean Grand Tour: Early Stuart Travellers in Europe (I.B. Tauris, London, 2014). ISBN 978 one 78076 783 3

- Lisa Colletta ed. (2015), The Legacy of the K Bout: New Essays on Travel, Literature, and Culture (Fairleigh Dickinson Academy Printing, London, 2015). ISBN 978 1 61147 797 9

- Sánchez-Jáuregui-Alpañés, Maria Dolores, and Scott Wilcox. The English Prize: The Capture of the Westmorland, An Episode of the 1000 Bout. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0300176056.

- Stephens, Richard. A Catalogue Raisonné of Francis Towne (1739–1816) (London: Paul Mellon Centre, 2016), doi:10.17658/towne.

- Geoffrey Trease, The Grand Tour (Yale University Press) 1991.

- Andrew Witon and Ilaria Bignamini, M Tour: The Lure of Italian republic in the Eighteenth-Century, Tate Gallery exhibition catalogue, 1997.

- Clare Hornsby (ed.) "The Affect of Italian republic: The G Tour and Beyond", British School at Rome, 2000.

- Ilaria Bignamini and Clare Hornsby, "Digging and Dealing in Eighteenth Century Rome" (Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2010).

- Roma Britannica: Art Patronage and Cultural Substitution in Eighteenth-Century Rome, eds. D. Marshall, G. Wolfe and S. Russell, British School at Rome, 2011, pp. 147–lxx.

- Henry S. Belden Three, Thou Tour of Ida Saxton McKinley and Sister Mary Saxton Barber 1869, (Canton, Ohio) 1985.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grand Tour. |

- The Grand Bout page for English course taught at the Academy of Michigan

- Grand Tour online at the Getty Museum

- In Our Time: The Grand Tour: Jeremy Black, Edward Chaney and Chloe Chard

- Wanderings in the Land of Ham by a daughter of Japhet, London : Longman, Dark-brown, Greenish, Longmans, & Roberts, 1858. A description of an Oriental Grand Tour at the Internet Annal Digital Library.

montefioreslosicessir1967.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_Tour

0 Response to "Exposure to the Art Treasures of Italy on the Grand Tour Played a Major Role in the Rise of"

Post a Comment